From Kongming to Tianjin: Jian Bing

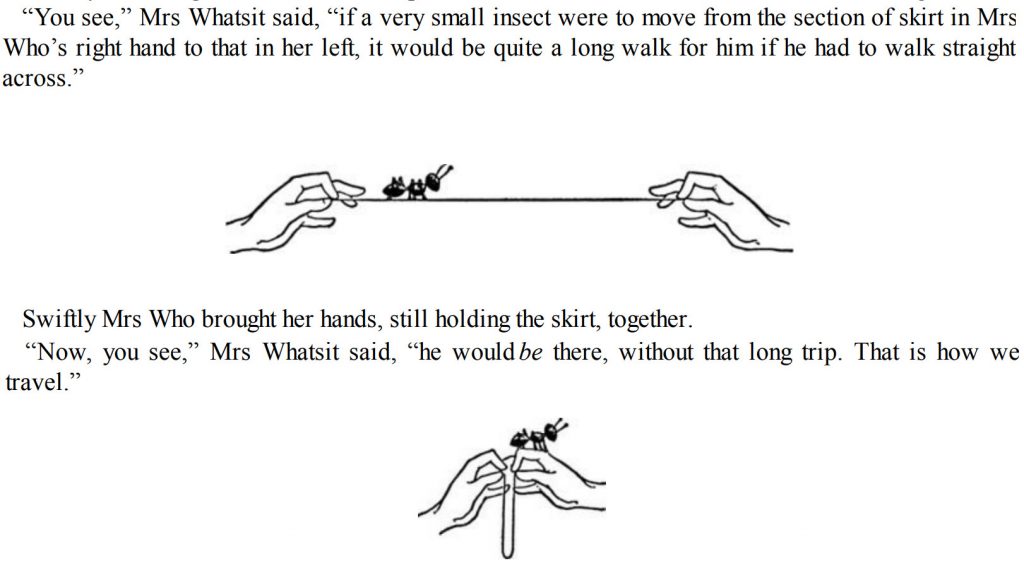

Jian Bing is a Chinese street food commonly eaten for breakfast, a kind of crepe cooked with egg and topped with ingredients and sauces before being folded in a way that is more sandwich-like than burrito-like. Is it a sandwich? A wrap? An abstract topological carbspace? An edible demonstration of the multidimensional universe, like a tastier version of Mrs. Whatsit’s and Mrs. Who’s tesseract explanation from A Wrinkle In Time?

The pancake itself, simply called jian bing, has its origins in Northern China around 2000 years ago during the Three Kingdoms period, according to local legend. The story goes that Zhuge Liang (called Kongming as his “courtesy name“), the strategist of the Shu Han faction led by Liu Bei, encountered the issue of how to feed an army when his soldiers lost their cookware. He solved the issue by having them mix a thin batter of water and flour and cook it on their shields over a fire, resulting in a thin pancake.

If, like me, you have gotten all your knowledge of the Three Kingdoms era of Chinese history not from the actual study of history or even from reading the popular historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but exclusively from the Dynasty Warriors series of video games, this will not surprise you. Zhuge Liang was a wily one, and not even death could stop his plans.

The version of jianbing stuffed with many tasty things that we are concerning ourselves with today is also called jianbing guozi, though often referred to simply by the simpler jianbing, and was first documented (according to Wikipedia) being served in the northern city Tianjin by the newspaper Ta Kung Pao in 1933. You may have seen jianbing in a season 20 episode of Top Chef last year, or in some other media–I feel like I had seen the process depicted in many a video before I ever caught it in person. It goes like this (follow the photos below for photos of the process at Jian in Chicago’s French Market as they recently made me a pulled pork jianbing):

A thin layer of crepe batter is spread around the griddle surface, then an egg is cracked on top, roughly broken, and spread around as well, maintaining the separation of egg yolk and white rather than being fully scrambled. Sesame seeds and scallions (or sometimes chopped cilantro) are sprinkled on top and adhere to the tacky egg. Then, once the crepe is sufficiently set, it’s flipped. A brown sauce containing some combination of bean paste and chili sauce, perhaps even some hoisin sauce, is spread around the surface of the jianbing, then 2 crisp fried crackers (bao cui, though sometimes long cylindrical Chinese donuts called Youtiao are used instead). Along with the crackers, other toppings/fillings are usually added, such as lettuce or meats or pickled mustard greens. In this particular case, red cabbage, pulled pork, and mayonnaise. Then the jianbing is rolled up and folded over and cut into sections and slipped into wax paper or, in this case, a cardboard clamshell container.

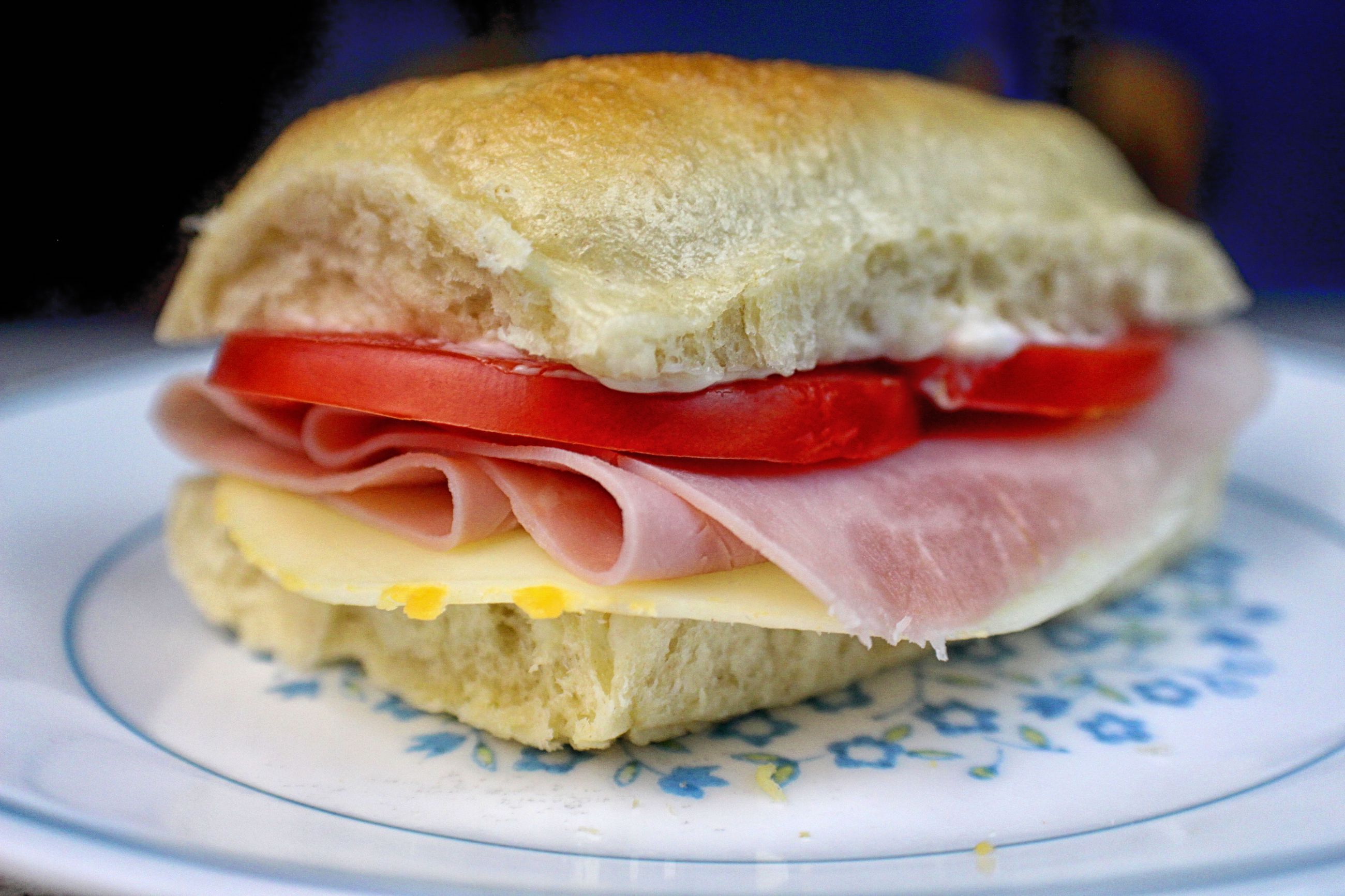

Here’s what it looks like once they hand it to you and you make your way to a nearby table to eat the thing.

It’s colorful, though it doesn’t look particularly pretty. It tastes good though, and has an interesting variety of textures, the soft and moist outer layer of egg and crepe studded with toasty sesame seeds and little pungent bursts of scallion barely holding the crisp fried crackers and cabbage inside, all surrounding a mass of pork, its silken strands taking with the sweet and pungent fermented soy flavors of the brown sauce.

It’s good. It’s filling. But better yet is the “classic” version, with only lettuce added to the crisp bao cui before the jianbing is folded around it.

There’s something more focused about the lower-key classic jianbing–the same soft rich outer wrap, the same crisp crackers providing shape to the dish, the same sweet and pungent soy-based brown sauce, with only crisp wisps of lettuce inside. There is no hunk of meat anchoring the wrap/sandwich–rather, the wrap and its trappings are the focus, and should be.

In addition to Jian, there is one other place I know of in the Chicago area that makes jianbing. It’s called Monkey King Jianbing, and was originally located in a small space on the second floor of an office building at Archer and Canal, just outside Chinatown proper. At least that’s where Nick Kindelsperger found Monkey King when he wrote about them for the Tribune 2 years ago. These days, they’re located in Skokie, on the same stretch of Dempster Avenue that boasts locations of Hub’s Restaurant (famous for an extremely dumb and pointless SNL skit from the 90s that I still quote, mostly because I used to live a few blocks from their Lincoln Avenue location), NY Bagel & Bialy (whose Touhy location in Lincolnwood is still my go-to spot for good bagels in the Chicago area), and Poochie’s, whose char salami sandwich got a mention in my previous post on this site.

Monkey King’s crepe cooker sits back in a kitchen out of view, so their process is not as transparent as that of Jian making things in plain view in a market kiosk. But their crepes come out huge and beautiful and Instagram-ready, cut in half with laser precision and neatly stacked in similar cardboard clamshell containers. As with Jian, I really appreciated their classic version, which wrapped black sesame-studded crepe and egg around lettuce and crisp crumbles of bao cui.

When I asked the young lady behind the counter to recommend to me the one variety of Jianbing they served that I should not miss, she recommended the “Meat Floss and Beef Hot Dog” flavor as their most popular.

The sung or meat floss is a more delicate filling than pulled pork, and though it is by definition completely dry, it doesn’t make the jianbing unpleasant or difficult to eat. In fact it works quite well as a filling. As for the hot dog, it was fine, the texture tight and snappy but easy to bite through and the flavor working well with the other jianbing ingredients–the egg, the sesame, the crepe, and even the pungent bean paste. It made me wonder how well a meat product like SPAM would work in a jianbing. And in fact Jian does offer that as a filling option.

But it was time for me to try making jianbing myself.

Bao Cui should be easy enough to make–it’s a simple thick mixture of flour and water much like pasta dough, rolled out thin, cut into sheets, and deep-fried. A similar product can be achieved by laying wonton wrappers out flat and deep-frying them.

Like so

Many of the recipes I’ve found for jianbing use all-purpose flour alone, but most sources describing the dish will also mention an alternative flour in the batter, mung bean flour or millet. I used a recipe with some millet in it along with a relatively low-protein all-purpose flour. I found the batter difficult to work with on a crepe pan–it would break if I tried using the crepe spreader on it at all. So I simply put a little more batter in the pan than I thought it needed and used the pan-swirling method to get full coverage, then let the crepe batter set for a few minutes before carefully breaking an egg on top and spreading it. I used both toasted and black sesame seeds along with scallions to season the egg. It took me some practice to get to the point where I could flip one of these reliably. My main takeaway was that making these at home was a slower process than what they were doing at Jian.

My sauce was a mixture of black bean sauce, hoisin sauce, and chili/garlic paste with a little water to thin it to a spreadable consistency that would not break the crepe when I brushed it on. In addition to thin-sliced of pan-fried spam and the crisply deep-fried wonton wrappers, I used a handful of finely-sliced napa cabbage for each jianbing.

To fold, I used my long thin crepe-flipping device (actually my wife’s cake icing spatula, which worked well enough for the purpose) to flip one side of the crepe up over the central pieces of cracker and spam, then the other side. Then I folded one end over the other, resulting in something roughly the size and shape of a sandwich.

The spam was sliced fairly thin, 12 slices to a tin, but adding 2 slices to each side turned out to be excessive, so instead I put one on each side and offset them so there was full spam coverage in the jianbing, and this ratio was just right. The saltiness of the spam was complimented well by the sweet, salty, and pungent black bean sauce as well as the chili pepper heat and even the crunch and slight mustardy / horseradishy bite I detected in the napa cabbage.

I liked the spam jianbing. But I’d probably have liked it equally well with just the napa cabbage and no spam at all. There’s something about this combination–a grassy, slightly nutty crepe enhanced by the nuttiness of the toasted sesame, rich egg cut by the pungent scallion and black bean sauce, the crispness of the fried cracker and the raw cabbage contrasting the soft, delicate crepe surrounding them. Jianbing is a popular breakfast food in China but I could happily eat these for any meal.

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

I thought you might have gone in the direction of Chinese Cooking Demystified and done crossover Chinese/American style Mexican – look at their video “Jianbing but with Taco Bell stuff” (I think it was their April fool video a few years ago, but it’s a real recipe, just not as serious as their usual style (