Scotch Woodcock: None Of The Above

The sequence of a multi-course dinner, according to Victorian era Toast Sandwich auteur Mrs. Beeton, was as follows:

- Hors d’œuvre

- Soup

- Fish

- Entrée

- Remove or Relevé

- Roast or Rôti

- Entremets

- Vegetables

- Sweets

- Savouries

- Dessert

- Coffee

The style of laying out course after course in sequence, directing the disposition of the degustation one might say, was a Russian innovation, displacing the French method of simply filling a table with every conceivable comestible and allowing the guests to have at it. The French would have their say though–the course names mainly came from their language.

There had been some drift in the names and styles of the courses over time, and would be more throughout the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The Hors d’œuvres were by 1861 simply a series of cold appetizers but had once also encompassed the small, composed warm plates that were in that time considered Entrées. Remove referred to a great spit of meat, while Roast or rôti was a secondary course of roasted fish or fowl. The Desserts of the time were cheeses, fruits, and nuts, though perhaps some candied fruits and small cakes or cookies would be set out as well, while the Sweet course consisted of puddings and ices, jellies and creams. Soups, Coffee, and Vegetables all seem self-explanatory. What in the world, though, was the Savoury course?

From roughly the mid-19th Century to 1940, England–and apparently nowhere else in the world–adopted this savoury course toward the end of a meal as a way to cleanse the palate after the sweets and before the port and cigars came out. Savouries consisted of 5 basic types–cheese savouries, mushroom savouries, egg savouries, shrimp and lobster savouries, and croûtes, or toasts. It is likely no coincidence that these match closely the list of foods high in glutamates, the compound responsible for the umami flavors that are considered “savory.”

Welsh rarebit, discussed previously on this site, was considered a savoury dish, as were cheese straws, the bacon-wrapped oysters called Angels on Horseback, and their more sinful counterparts, the cheese-and-almond-stuffed, bacon-wrapped dates called Devils on Horseback. Scotch Woodcock was another.

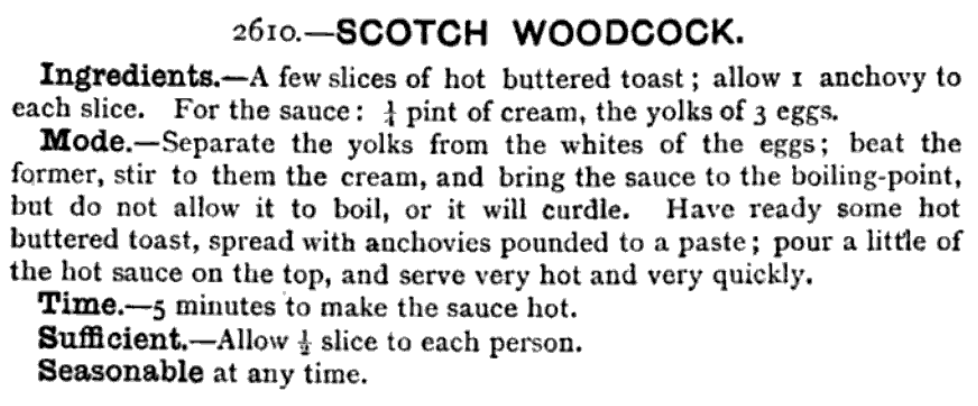

Often described these days as toast with anchovies and scrambled eggs–though anchovies and scrambled eggs describes an entirely different savoury dish–the original recipe from Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management features something more like a cream sauce, thickened with egg yolks, poured over toast and mashed anchovies.

It sounds easy enough. We start with a tin of anchovies.

When they say “pound” the anchovies–that is precisely the best approach to take. I tried to use a fork to sort of half-mash, half-mince the little fishies into something resembling a paste but had to get out the stone pestle from my molcajete to get them started. I added a little of the olive oil from the tin to give them a more spreadable consistency.

Also, keeping the sauce from curdling is more complicated than simply not letting it boil, but with slow heating and several minutes of constant stirring, alternating between a whisk and a silicone spatula, I managed to keep it at least somewhat smooth, resulting in this:

It’s a fairly simple snack–triangles of toasted bread, spread with the intensely salty and savory pounded anchovies, then covered with the rich but unseasoned cream sauce, a combination of textures and flavors that leans heavily into umami territory but doesn’t present many other flavors.

I find myself not wanting to eat much more than a bite or two of it. I suppose that is all one would really want toward the end of a dinner featuring eight or ten courses, and it might be just right to change things up after a plate of sticky toffee pudding or spotted dick.

Speaking of English food items with funny names…

This is Patum Peperium or “Gentleman’s Relish,” which I assure you is not a euphemism for anything unsavory. On the contrary, it is an extra-savory spread made from anchovies and spices, and features in many more modern versions of Scotch Woodcock. As I researched this writeup, one site I kept returning to, BritishFoodHistory.com, had a Scotch Woodcock recipe that seemed good and used this Gentleman’s Relish, which I’d been looking for an excuse to acquire for some time.

The British Food History recipe doesn’t specify which toast to spread your relish on–I used a good, crusty loaf from Damato’s Bakery. Yes it’s an Italian bakery, not an English one–what of it? It also called for a much more even ratio between cream and eggs, using whole eggs rather than just the yolks, and seasoned this custard with cayenne and nutmeg, rather than not at all. Finally, and best of all, it had this very encouraging caveat regarding heating the custard: “Don’t worry if there are a few small lumps of cooked egg: it’s very forgiving.”

Well my custard turned out quite broken, but as the entire mess then gets put under a broiler to set, that turns out not to be the end of the world.

There were things to like about this version of the recipe. The nutmeg and cayenne give the custard a more aromatic character than the cream sauce from Mrs. Beeton, and allowing the custard to set under the broiler makes the sandwich a neater one, and gives it some additional character from the browning of the eggs. The Gentleman’s Relish lacks the punch of the pounded anchovies though, and I found myself missing that as much as I appreciated the good qualities of the sandwich. Again, a few bites was more than enough to satisfy me.

Something that combined the additional seasoning and a more substantial presence of egg with the (sparing) use of the power of anchovy was called for. Also, possibly something a little spicier. I found it in the New York Times recipe for Scotch Woodcock, which hews far closer to the modern conception of this dish as “anchovies with scrambled eggs.” It calls for anchovy paste (I used the last of my Gentleman’s Relish) topped with seasoned scrambled eggs and 2 fillets of anchovy. I used these Italian anchovies, packed in olive oil with red chilies.

For this recipe, the anchovy paste is spread directly on toasted bread without any butter. The eggs get a little cream added along with salt and pepper, then are cooked with melted butter until just set. Then the eggs are topped with 2 crossed fillets of anchovy, and the dish garnished with “parsley or watercress.” I used chives, as that’s what I had. Also, chives are delicious with eggs.

I liked this version as well as or better than any of the other versions I’d made. I still found it hard to eat more than a few bites. Even with some additional dimensions added, whether the aromatics from the British Food History recipe or the substance of the eggs and the slight pungency of the chives from this NYT recipe, the dish was missing something. Anything, really, other than… savory. Pickled onion, perhaps. Hot sauce. Some hot English mustard. Some peppery arugula or cress, a little bitter endive or celery, the perceived sweetness of shaved fennel. Something to break up the umami monotony.

I can’t hate scotch woodcock too much though. The dish is, after all, doing its job only too well, providing an intensely savory bite or two, resetting the palate before the wine starts pouring. The fact that I am not eating it at the tail end of a 12 course meal before tying one on with the boys is, of course, entirely my own fault.

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

Ya know, I’m thinking those little rye bread squares that they sell in the deli area of most supermarkets might work here. Just a small bite of this could be good – but I think garlic is necessary. Maybe horseradish?