This Lao Baguette is no Bagatelle: Khao Jee Pâté

Directly north of the Malay peninsula, home of the Kaya Toast we just wrote about, lies the mainland of Southeast Asia. South of China and east of the Indian subcontinent, this corner of the world is home to Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and, landlocked between the others, Laos.

The Wikipedia article on Cambodian cuisine starts by drawing a distinction between Cambodian cuisine and Khmer cuisine–Cambodian being a national identity and Khmer being an ethnic identity. It’s worth bearing this distinction in mind with the other cuisines of the region as well. National borders in the area are somewhat arbitrarily and irregularly drawn–Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos occupy the geography known during the colonial times as French Indochina, while Myanmar was once British Burma and Thailand was the independent nation of Siam. But the Khmer, while living mostly in Cambodia, are also spread through Vietnam and Laos. Similarly, the Lao, an ethnic identity distinct from the national identity of Laotian, are spread through Laos and Northern Thailand. When including the ethnically Lao Isan people, there are in fact more Lao people in Thailand than in Laos.

So though the proponents of Lao cuisine, or Cambodian or Thai or Vietnamese cuisine, may draw hard distinctions between the culinary styles of the area, it is easy for an outsider to see more of the similarities than the differences. This is in large part because of the way the lines are blurred between the national and ethnic identities. For example, a typical Thai restaurant may serve plenty of Lao dishes simply because there are so many Lao people in Thailand that Lao cuisine is part of the landscape there. Sticky rice is a major part of Lao cuisine, and it would be an unusual Thai restaurant in the US that did not serve sticky rice in some capacity. Larb, an intensely flavored salad of minced meat with chilies and herbs and shallots dressed with fish sauce and lime juice and sprinkled with toasted rice powder, one of my favorite things to order at a Thai restaurant, is in fact a Lao dish. So is Nam Khao, another intense sour, salty, and spicy salad featuring crispy fried bits of curry-seasoned rice and a fermented ham-like sausage.

While the similarities between Lao and Thai cuisine have to do with the ethnic spilllover between these nations, some commonalities between the Lao, Cambodian, and Vietnamese cuisines are instead a legacy of their shared colonial past. One common remnant of colonial culture left over in each of the countries that formerly made up French Indochina is the French baguette. In Vietnam, these baguettes are called Bánh mì and are often sold at street stands, slit open and stuffed with meats, vegetables and herbs to make the well-known sandwich also called Bánh mì. In Cambodia the baguettes are called Nompang and may be sold stuffed with papaya and/or pork with chili peppers and other vegetables to make sandwiches that again are known as nompang.

Laos’ version of the baguette sandwich is known as Khao Jee Pâté. In the Lao language, the word Khao means a grain preparation, which more often than not would be sticky rice. The word Jee means that the rice is roasted or baked. Khao Jee then is a phrase that may be used to indicate bread. Confusingly though it is also the name of a grilled sticky rice preparation, where the rice is formed into patties, coated with a seasoned egg mixture, and grilled until crispy.

These of course are not the sandwiches we are speaking of, though they’re a tasty-enough snack. Many of the descriptions or recipes I’ve found online for the sandwich Khao Jee Pâté sound much different than what I’ve come to expect from a banh mi–they call for watercress and tomatoes, for example, or cheese and onions. Watching videos of the sandwiches being prepared by street vendors in Laos though shows a process and a result very similar to banh mi but with intriguing differences–a baguette is slit open, smeared with pâté, topped with more meat products–bats of julienned pork roll, sausages, slices of ham, pinches of pork floss–along with julienned carrots, cucumber, cilantro, and chili sauce. The vendors then smash this excess of fillings down with their knife blade and wrap the sandwich in paper or stuff it into a bag before handing it off to the customer.

When I’m researching a sandwich, if at all possible I like to try and find a place nearby that serves the sandwich and try a vendor-prepared version, under the assumption that they must have a better handle on what a sandwich is about than I do. For the Khao Jee Pâté, the nearest vendor I could find offering one was Mekong Cafe in Milwaukee. Their website has a page dedicated to Khao Jee Pâté and Banh Mi sandwiches, where the Khao Jee Pâté is described as similar to banh mi, and the terms appear to be used somewhat interchangeably, perhaps for the ease of their customers. As Milwaukee is an easy and semi-frequent day trip for us, less than 2 hours to drive, it was an easy call to make.

Mekong Cafe is a corner bodega on the west side of Milwaukee featuring a selection of Asian dry goods, prepared foods, and a carryout menu. Mindy and I stopped by on a Sunday afternoon and ordered Nam Kow, Mekong’s version of the crispy rice salad mentioned previously, a bowl of noodle soup, and the Bang Banh Banh Mi, which was the sandwich they offered that most resembled a classic Khao Jee Pâté according to our cashier. We also picked up some premade sticky rice with mango and some snack foods along with beverages. There is no dine-in service at Mekong Cafe even in non-Covid times it seems, and as it was a cold day, we picnicked in the back of our car outside the shop.

Mindy’s noodle soup was not easy to either eat or photograph in a carryout, backseat picnic situation. The Nam Kow though was a decent version, more rice-heavy than some but with that combination of flavors and textures that makes it such a great dish–the crunch of the crisp fried rice and the peanuts, the soft, sour, salty, fatty sausage, the bright cilantro, the spicy Thai chilies, the sour and salty lime juice and fish sauce dressing. The salad was served on a bed of lettuce that could be used to scoop up the rice into lettuce wraps but we dug in with forks instead, tearing off pieces of lettuce as needed to temper the intensity of the salad.

The light in the car wasn’t ideal to capture the contents of the sandwich, but you can see the cilantro, some carrot and daikon radish, cucumber, pork roll, another more reddish meat, and a glimpse of pork floss on the left there. It was not a sandwich that showed restraint, balanced quite a bit more toward meatiness than most of the banh mi I’ve had. Also, rather than the raw slices of jalapeno that are common garnishes for banh mi, this sandwich used a chili sauce, Shark brand Sriracha sauce, to liven things up.

What, what’s that? A question? You in the back, yes? What is pork floss?

Digression #1: Pork Floss

Pork floss, called Rousong or Yuk sung in various Chinese languages, is called Moo foi in Laos. It is pork that has been cooked slowly enough for the collagen holding the muscle fibers of the meat together to dissolve completely. Those fibers are then teased apart into individual strands and dried into a product with a texture resembling a coarse cotton ball.

Similar products are also made with chicken, beef or fish, especially in Southeastern Asian countries with majority Muslim populations like Malaysia or Indonesia. Pork floss appears to be more common though, or at least is what I can find more easily at Asian markets in the Chicago area. The flavor is salty and slightly sweet, and the floss dissolves into a pleasantly chewy mass as it takes on moisture in one’s mouth. It’s good stuff, not a featured player but a tasty and unusual garnish for many Asian dishes including this sandwich.

Banh Mi at Nhu Lan

The combination of meats in the Bang Bang Banh Mi from Mekong Cafe–2 kinds of pork roll with pate–seemed pretty similar to the classic style of banh mi as served by my favorite banh mi shop in Chicago, Nhu Lan Bakery in my old neighborhood of Lincoln Square on the far north side.

In addition to selling fantastic, made-to-order banh mi and the best Vietnamese style demibaguettes that I’ve had, Nhu Lan also has a cooler full of spring rolls, steamed dumplings, interesting premade drinks containing various seeds, gels, and grains, and other Vietnamese snacks.

When it comes to Nhu Lan, I am all in. I am going to buy sandwiches, I am going to buy bread to bring home, I am going to peruse the coolers and pick out interesting treats to bring home as well. I did want to focus today on the sandwiches though, particularly the #1 “Nhu Lan Special” with ham, head cheese, pâté, and pork roll; and the #5 with pâté and pork belly, as these combinations seemed the closest to what I was learning about Lao Khao Jee Pâté.

The #1, which I thought would have pâté in it, did not, or at least the pâté was unnoticeable under the ham, pork roll, and head cheese. The #5, however, had a noticeable schmear of pâté that stood out, despite the strong-flavored char siu style pork belly it was served alongside. In concept, either one of these, or perhaps some amalgam of the two, would have been similar to what I had from Mekong Cafe. In practice, though, the balance was different. Again, the Khao Jee Pâté sandwiches seem to skew meatier.

I would have to make my own. I picked up demibaguettes from Nhu Lan, because I was there and because it is exceedingly unlikely that I will ever bake a better piece of bread than what they are already putting out–a light but crisp crust and a crumb that is light enough to conform itself around a sandwich’s contents but sturdy enough to handle the juiciest of banh mis. I also picked up a couple different kinds of pork roll out of their cooler, which would serve for the basic meats of the sandwich.

Now I would just need to make some Lao-style pâté.

Digression #2: Pâté

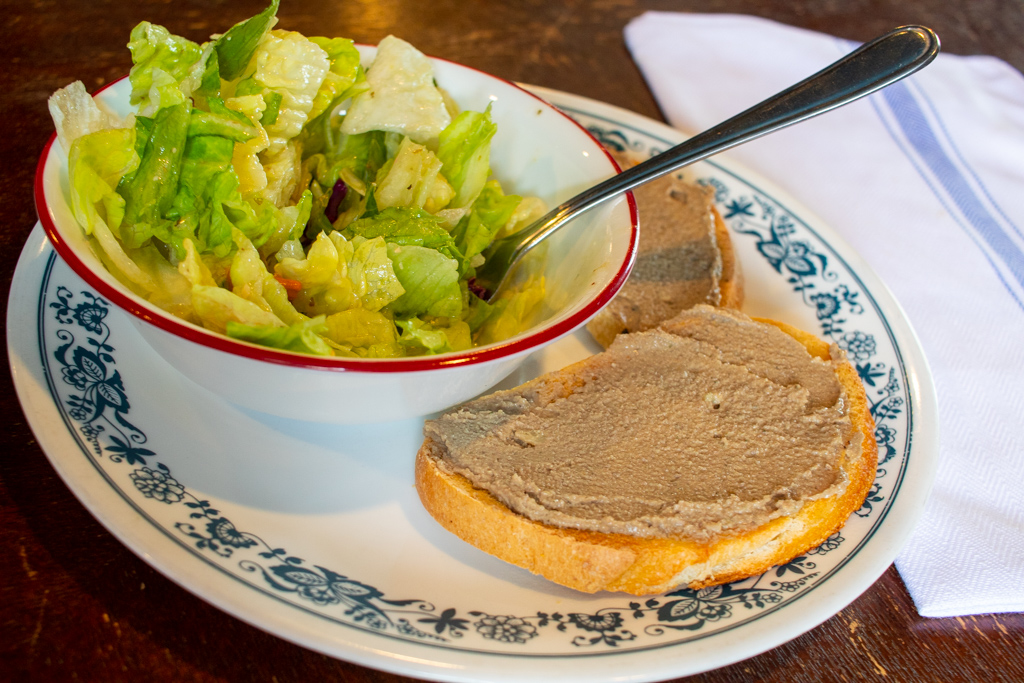

The pâté recipes I’ve found can basically be split into two basic styles. One of them is more of a fancy, charcuterie type terrine, where a forcemeat is made of raw liver and fatty pork meat with seasonings, aromatics, perhaps some additional fats, and then slowly steamed in small loaf pans until cooked through and thickened to a state that is either spreadable or sliceable. The other is more of a home style preparation where the meats and aromatics and fats are cooked together, then whipped in a food processor or blender before chilling under a layer of melted butter to aid in preservation. For whatever reason, the latter method appealed to me more for this project, and I followed this recipe for a Lao-style pâté fairly closely with only a few minor tweaks, including doubling the recipe, using palm sugar instead of refined sugar (I had some leftover from making Kaya), and adding just a bit of padaek, a chunky Lao fish sauce I bought that is crazy strong. I’m not just sure how I’m going to use a whole bottle of it but a splash of it here had less of an impact than I thought it would.

It would make a more attractive presentation if I’d clarified the butter before sealing the pâté in with it, but the flavor is the thing, right?

The pâté is quite mild, with a slight amount of the metallic liver flavor present but equally porky and citrusy with coriander and thyme aromas cutting through what might otherwise be monotonously rich. Still, it’s best to serve it with some pickles, or a light salad.

In the case of Khao Jee Pâté, we’ll get both. Every preparation I saw used either fresh or lightly pickled julienned carrots, so I prepared some of those as well, simply dissolving a small amount of salt and sugar in a mixture of water and rice vinegar, then pouring the hot solution into a jar full of julienned carrots and refrigerating them overnight. Between that and the cucumber and cilantro, we should have both pickles and salad covered.

However, the preparations I’ve seen have all used a chili sauce as well. In the case of the Mekong Cafe version, it was a Sriracha sauce. In the Youtube videos, sometimes it appeared to be a liberally-applied squirt of Sriracha and others it appeared closer in texture to a Sambal Oelek. When I look up Lao chili sauce recipes though, only one phrase comes back over and over again.

Digression #3: Jeow Som

Jeow Som is a Lao chili sauce that appears to be very similar to, if not the exact same thing as, the Hmong chili sauce that has haunted me ever since my first trip to Hmongtown Marketplace in St. Paul, Minnesota several years ago. I have made my own version of it several times with varying amounts of success. However, this week I followed along with this Youtube video recipe–to an extent–and have found perfection.

We start with a couple spoonfuls of sugar, a half teaspoon of MSG, several garlic cloves, a small handful of Thai chilies–as many red ones as I had along with a few green ones–and some cilantro stems and leaves

We mash this mixture into a paste in a mortar and pestle or, better yet, a stone molcajete like this one, which provides a rough surface to help abrade the vegetable matter and speed the process of pulping it. In any case, even with a smooth mortar and pestle, the granulated sugar should provide enough abrasive power to make short work of the chilis, garlic, and cilantro.

Once the chilies etc. have been mashed into a paste, we add several tablespoons of fish sauce and the juice of a couple of limes, then taste and adjust. I believe I used 4 tablespoons of fish sauce and the juice of 2.5 limes.

This sauce is magical. You can put it on literally anything and that thing will then taste better. I would seriously eat Jeow Som flavored ice cream. Well, I mean I’d give it a shot anyway. This sauce is, all at once, hot, sour, salty and sweet. an encapsulation of the flavors that make the cuisine of Southeast Asia so exciting. In fact, I have been eating it on toast with pâté for breakfast every day recently.

Khao Jee Pâté

As mentioned, I bought 2 kinds of pork roll at Nhu Lan. One is a typical Vietnamese banh mi ingredient called Chả lụa, which is a mildly seasoned pork forcemeat, wrapped in banana leaves and steamed. This is also known as mu yo in Thai cuisine, and it appears very much like the “Lao bologna” that is used in many of the Khao Jee Pâté descriptions I’ve seen.

The raw pork paste from which Chả lụa is made is sometimes prepared in other ways. When the entire sausage is deep-fried rather than wrapped in a banana leaf and steamed, the resulting pork loaf is called chả chiên. I had bought both, and though they are basically the same meat, the textures and flavors are quite different. The chả lụa is softer, with a green tinge to the outer layer and a vegetal, tea-like aroma from steaming in the banana leaf. The chả chiên is chewier and takes on some of the character of the oil it is fried in. I cut the chả lụa into slices and the chả chiên into long narrow bats as this seemed to best present the uniqueness of each meat.

I also pulled out a secret weapon–Lao sausages, which I’d bought at 5XEN Market while we were in Milwaukee visiting Mekong Cafe. These have a similar but less aggressive flavor profile to my much-loved Hmong sausages–lemongrass, galangal, makrut lime leaf. They would be a fantastic way to sneakily introduce someone to southeast Asian flavors, as they look and feel familiar–sausages are sausages, right? But they taste different from any Western sausages in interesting and exciting ways. I grilled these over charcoal and sliced them on the bias for serving in the sandwiches.

Ideally, before making a baguette sandwich of any kind, unless that bread is still warm from baking, I like to put it into a 350˚ F oven for 5-6 minutes, just to make sure that crust is a little crisp. It also helps soften the crumb, and makes the overall sandwich-eating experience just a little better. This is of course entirely one man’s opinion and you should eat your sandwiches whatever wrong way you choose to.

For the Khao Jee Pâté, spread a thick layer of pâté on at least one side of the bread. I like to use Kewpie mayo as well–this is entirely optional, as pâté is essentially a kind of meat mayonnaise. Also, in most of the videos I saw, they put at least some of the carrots directly against the pâté layer. It makes sense to me, get the pickles right there to cut some of the pâté’s richness.

For my initial attempt at a sandwich, I kept it simple. Pâté, Kewpie mayo, carrot, chả lụa, chả chiên, cucumber, a little more carrot, cilantro leaves and stems, and some of the fantastic Jeow Som chili sauce. This is perhaps the best way to showcase the essentials of the Khao Jee Pâté sandwich. Both the chả lụa and chả chiên are relatively restrained flavors, allowing the pâté to come forward. Since the meats are relatively restrained, the balance is more banh mi-like, with a healthy presence of plant matter-the fresh crisp cucumber, the zesty cilantro, the mildly sweet, sour, salty pickled carrots.

Then the Jeow Som shows up and turns everything up to 11. The glory of this sauce is not necessarily that it has such a strong flavor of its own–it does, for sure, and could certainly overwhelm things if used in excess. But used with restraint, it adds a little heat, a little tart, a little zip, while simultaneously making everything else in the sandwich taste more like itself. The sauce was a little too hot for my family, and after tasting mine they requested their sandwiches without. They don’t know what they’re missing. This sauce is magical.

For my second Khao Jee Pâté, I used the Lao sausage. While the Lao sausage may be mild when compared to the Hmong sausage I usually buy there, it is bursting with flavor compared to the pork roll. These sausages, when I buy them prepared from a food vendor, often come with a sauce much like the Jeow Som I’m using on this sandwich, so that is a natural combination. The pâté and remaining ingredients fall into place and it’s a good sandwich but

But I’m not quite there. The Khao Jee Pâtés I’m seeing online, and the one I bought from Mekong Cafe, they are using 3-4 types of meat at least, and they may or may not be using quite enough vegetables to balance that out, but they’re going crazy with the sauce to make up for it. I want to make one of those.

So I start with that magically perfect Nhu Lan demibaguette, a thick layer of pâté, and the unpredictable squiggles that one gets from a little plastic squeeze bottle of Kewpie mayonnaise.

I keep talking about how these sandwiches need more vegetables, but what am I doing about it. Nothing, really, apart from adding some lettuce this time along with what looks like it might be the last of my pickled carrots! (gasp)

One could probably make a fine Khao Jee Pâté with a whole sausage rather than these thin slices, but would it stack as nicely on the slices of chả lụa? Perhaps next time I will find out, but for today we opt for edibility.

We add the cucumber, we add the cilantro. We fish around in the jar of pickled carrots for the last few shreds remaining and add those as well.

Then, the crowning meat–pork floss.

The pork floss makes a conveniently visible platform on which to spoon a somewhat thicker layer of Jeow Som than I have been using previously.

And that is it! The ultimate Khao Jee Pâté. Or at least the ultimate one that I would be making. Ultimate in the sense of last, as I was now out of carrots and out of demibaguettes. But what a sandwich!

Despite this sandwich having 4 distinct types of meat, the sheer volume of greenery added by the lettuce gives it a semblance of balance, and the Jeow Som makes every bite explosive. The pork floss and chả lụa provide a sort of base level of porkiness off which the other flavors riff–the cucumber and cilantro pop! The sausage sings! The pâté and carrots have their own rich but acidic duet that is amplified by the umami boost of the sauce. That mayonnaise and lettuce can’t be forgotten–they’re there to remind you that this is a mere earthly sandwich rather than some Godssent manna.

That bread though. It’s nearly impossible to make a bad sandwich on Nhu Lan’s bread. (Kindly do not take this as a challenge. This bread deserves better from you.) Also, I’m using sausages that I purchased instead of made. So I can’t take too much credit. But let me urge you, if you take nothing else away from this writeup, please try Jeow Som. It’s easy to make and it’s unbelievably delicious. Happy Memorial Day everyone, and we’ll see you in June!

I like sandwiches.

I like a lot of other things too but sandwiches are pretty great

Recent Comments